A Beta Ray Bill Conversation Between Walter Simonson and Daniel Warren Johnson

The character's creator chats with the 'Beta Ray Bill' #1 writer/artist right in time for today's new issue!

The second-most famous wielder of Mjolnir. The right-hand man to the God of Thunder. And now, a warrior without his best weapon.

Beta Ray Bill is tired of playing second fiddle to Thor—and with Bill’s famous hammer, Stormbreaker, recently destroyed at the new All-Father’s hands, tensions are higher than ever. The Korbinite must strike out in search of a new weapon…and a new destiny. Assuming he can first defeat a Knullified Fin Fang Foom!

Find it all in today's BETA RAY BILL #1 by writer/artist Daniel Warren Johnson!

Featured in the letters page of this mighty mag is a conversation between Johnson and Beta Ray Bill creator, Modern Marvel Master Walter Simonson. Pick the issue up at your local comic shop for the raucous ride, and read the full version of Johnson and Simonson's discussion below!

Daniel Warren Johnson: I heard that you attended Amherst College (very near to where I grew up, actually!) and that you did a THOR fan comic just for fun. What motivated you to create that, and were there any standout moments during your college life that pushed you into pursuing professional comics?

Walter Simonson: When I was at Amherst in the mid-’60s, I discovered Marvel Comics, which had only been publishing Super Heroes for about four years at that time. THOR was the first one I discovered. I was already a Norse myth fan from childhood, so I was delighted to find a comic about the gods of the Vikings. I began reading all the Marvel comics (about eleven titles a month at that time). I was inspired to try drawing some comics—a few pages of DR. STRANGE, IRON MAN, ENEMY ACE—over the next couple of years. They were all fragmentary and got longer each time I did a new one. My first attempt with Dr. Strange was inspired by Steve Ditko’s final issue on STRANGE TALES [#146] wherein Eternity and Dormammu faced off. I loved the issue but thought it was too short. (It was half the issue of STRANGE TALES.) So I decided to do the long version of the final battle that I would like to have seen. It turned out that drawing comics was hard work, and I got about four pages done before I ran out of gas. But that was my first serious attempt to draw a comic as an almost-grown-up. I did have an idea for a Thor story based on the Marvel comic and Norse myths and my own thoughts but didn’t draw any of it then. During my time at Amherst, I wasn’t thinking about going into comics professionally. Originally, I was interested in becoming a vertebrate paleontologist, studying dinosaurs. By the end of college, I had concluded that that was not what I wanted to do. But I had yet to begin to think of pursuing comics as a profession.

Johnson: Could you talk a little bit about your time in NYC in the ’70s? What kind of creative culture was happening in comics with you and other creators?

Simonson: The ’70s and the first half of the ’80s were a great time to be in comics. There wasn’t a lot of money, but all of us who got into the business about the time I did (1972) really wanted to work in the industry. A lot of us thought comics was a dying art, and we wanted to be part of it while it was still around. Didn’t turn out that way, but we were full of enthusiasm and a friendly competitive spirit. Back then, there was no overnight delivery, no internet, no scanners. If you wanted to work in comics professionally, you pretty much had to live in NYC. That meant that I got to know all of the guys in my generation and a lot of the guys in previous generations whose work we all admired. When you were in the office, you saw all kinds of work being turned in by guys like Jack Kirby, John Buscema, Alex Toth, Joe Kubert, Russ Heath, Neal Adams, and all the stuff my generation was producing as well. It was very inspiring.

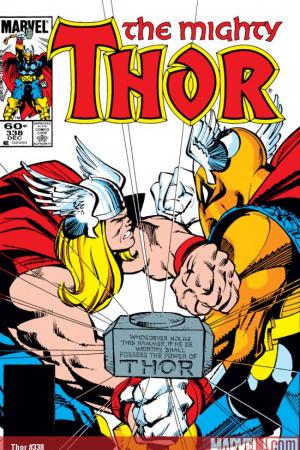

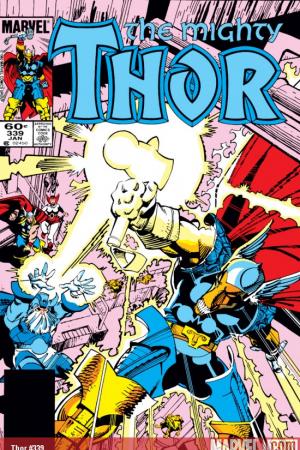

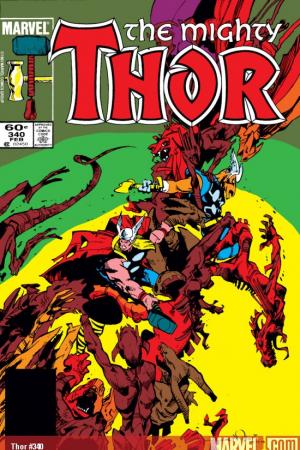

Johnson: The first arc of your THOR run that introduced Beta Ray Bill [#337-339] feels incredibly epic. What kinds of things were inspiring you when you created this story?

Simonson: Mostly I was just trying to tell a story that didn’t feel like it had been told before. Even then, Thor had about 20 years’ worth of continuity behind him. I had the idea of somebody else picking up the hammer to utilize the inscription on Mjolnir. It hadn’t really been done before, and everything else flowed from that idea. The backstory with Surtur was the tale I had developed in a rudimentary form at Amherst. I’d drawn perhaps 26 pages of it while I was in art school after Amherst, and then 14 years after that, I was able to use some of the original idea as the spine for my first 17 issues or so of THOR.

Johnson: Now Beta Ray Bill feels a little bit like a tongue-in-cheek character that is beloved but also maligned as a “horse-faced hero” and so on. Was there any sense of comedy about Bill when first creating him, or was the goal simply to make an intense-looking character?

Simonson: Nope. One of the things that I learned from Stan Lee and Jack Kirby is that you can get away with almost anything in a story if you keep a straight face. Bill was never a comedic character to me but more a tragic one who underwent torture and isolation to save his people.

Johnson: One thing I noticed when beginning this BETA RAY BILL miniseries is how hard Bill is to draw! After two issues, I’m finally getting the hang of it. Did you struggle with getting his shapes down after initially creating him?

Simonson: Bill worked out pretty well for me from pretty early on. I’ve simplified his face a bit over the years as my own drawing has changed. One thing about his facial structure is that relatively few artists understand his jaw as I drew it. It’s not a conventional jaw but a kind of rounded gap behind his teeth, inspired by a horse’s skull. But his jaw is not hinged conventionally like a horse’s jaw. No idea how that would work in real life, but that’s comics. The only real trouble I had was keeping the directions of the zigzag white lines on his torso consistent. I could never remember which ones went up and which ones went down. Now, of course, he has a different costume so that problem is no longer around.

Johnson: When looking through your work on that initial Beta Ray Bill story, it seems like your lines have an energy and spontaneity to them that feels organic and lively, and it’s one of my favorite things about your drawings. Your lines look like you had fun while making them. Is this a style that you’ve always had? Did drawing with deadlines ever make you change how you approach mark-making?

Simonson: The answer to your first observation about my drawing is that I love marks on paper. I want to make them look like they were slashed onto the drawing—not in a haphazard or sloppy way, but in a spontaneous way that imparts life to the drawing itself just though the marks that comprise it. As a result, I spend a lot of time making the work look spontaneous whereas in real life, as Jon Bogdanove once said, I have a very paper-intensive lifestyle. I go through a lot of stages to get to the point where the drawing looks (I hope) spontaneous.

As far as my approach to mark-making, the one serious effect I think drawing for comics has had on my output is that because of my early days in comics, now a long time ago, when comics were printed badly on newsprint, I developed a fairly bold style because I wanted to give the art the best chance to be reproduced on a page in a way that would still contain the energy within the drawings I was trying to achieve. I’ve gone to finer lines again and more rendering than I used 30 years ago, but some of that boldness in approach still remains, I think. Deadlines also played a role, in that writing, penciling, and drawing a book every month pushed me toward a bold approach without a lot of noodling.

Johnson: Nowadays it feels like it’s fairly rare for a person to do both writing and art duties on a comic book. What was the culture like back then for someone like yourself who was both the writer and the artist? What did you find to be the biggest challenges of taking on both jobs?

Simonson: Back then, pretty much all the doors were open to creative endeavors in mainstream comics by freelancers. Several of us took a crack at writing and drawing mainstream books, and there was the freedom to do so. Even encouragement sometimes. It was a fine time to be doing comics professionally.

And the biggest challenge is always the deadline.

Johnson: As a writer, what is the first step when beginning the creative process of making a new story? As an artist, do you think in visuals first, or start somewhere else?

Simonson: I don’t have a single method of starting a story. Sometimes, as in the case of Beta Ray Bill and THOR where I wanted a story that hadn’t been told before, the idea of Mjolnir’s inscription came to me as I was thinking about what I might do for my first story arc. In the case of Thor fighting the Midgard Serpent [THOR #380], it came as a flash of inspiration in which the entire story and the approach of using all splash pages literally burst above my head like a light bulb. Other stories I’ve had to drag out of myself. On books that I work on for a while, new ideas often occur to me. Sometimes it’s no more than a thought; sometimes it’s a whole plot. I just have to make certain I write everything down, as I’ve learned the hard way that ideas and plots like that are as evanescent as dreams, disappearing without a trace if I don’t capture them immediately.

As a comic book artist, I pay attention to the visual storytelling first when I begin to lay out a tale. It’s all about page design, eye direction, panel composition, and how best to tell the story. With my own work, I approach it “Marvel Style,” which means that I plot my story first, thumbnail the entire job next—a quick sketch of each page done on copier paper—and then write the script from my thumbnails so that I can see how the words and the pictures work together. Once I have a complete script, I blow up the thumbnails onto artboard, very loosely still, and then place the copy so I can be sure everything lines up. Then I start working out the visuals in detail—figures, costumes, backgrounds, architecture—everything that goes into creating a convincing space in which the story occurs.

Johnson: One of my favorite things about your art is your inclusion of sound effects and the typography used for them. Is this something that you would solely do, or did John Workman [Simonson’s frequent letterer, including on his THOR run] also contribute?

Simonson: I got interested in letterforms while I was at the Rhode Island School of Design after Amherst. There was a certain emphasis there on lettering in those days. Chancery cursive hand—an italic alphabet based on older letterforms—was popular for a time in the late Middle Ages. A classic pamphlet called La Operina was written in and about chancery cursive by Ludovico Vicentino Arrighi and published in 1522. Students were taught chancery from a translation of the pamphlet as a discipline, and I was interested enough in the subject that I pursued more knowledge of lettering while I was in school there. That knowledge informed my comics, and in my early professional work, I drew my own sound effects and title lettering. When John Workman and I began our collaborations, I found he could do what I wanted to do better than I could, so for the most part I handed the display lettering over to him. I write the titles and sound effects, indicate the size and placement on the art, and then it’s up to John to design and letter them.

Johnson: As a creator who has worked steadily for so many years, how have you managed to navigate different pop culture trends and different companies? What do you think has kept you relevant all these years?

Simonson: Stubbornness and dumb luck.

Johnson: Do you find it harder to make things as you get older? Or has the process stayed mostly the same throughout your career?

Simonson: It’s never really easy. And sometimes I feel now that I don’t have the courage of my youth as an artist when a lack of knowledge emboldened me to do all kinds of things that I wouldn’t try now. But I hope I make up for it by having learned a lot of tricks over the years. It’s also more difficult not to feel that sometimes I am repeating myself in drawing or storytelling solutions. But one does what one can.

Johnson: I’ve heard you’re a big fan of the Hunt 102 nib for inking. What other tools do you find yourself gravitating toward today? And please excuse my nerdy paper question: Smooth or vellum?

Simonson: I do rely on the Hunt 102 crow quill primarily, along with Pelikan Tusche A India ink. The only other tools I use for drawing are the occasional technical pen like a Rapidograph or a brush—generally a Raphael 8404 No. 2 or No.3. I’ll use felt tips or markers for convention sketches and such, but I generally stick to the traditional tools of the trade from long ago.

I use both plate and vellum finished paper, depending on how I want the job to look. I’m not sure anybody can tell the difference but me, but there is a quality in the drawing I feel the paper enhances differently by its nature. I often use vellum for covers because those are big images, and I sometimes feel they can use a little extra texture.

Johnson: Out of your entire comics career, what are you most proud of? Are there projects you look back on with a grimace or see things that you would have liked to draw or write differently?

Simonson: I really haven’t done any jobs where I felt I just sloughed off the work. I pretty much always tried to do the best job I could in the time allotted to me. I don’t fret about my old work because I know what I put into it. There is, of course, stuff I wouldn’t mind redrawing, but it’s too long ago and too far away. And it was the best I could do then. There was one head in a job about the Alamo very early in my career that I’d give a nickel to be able to go back and redo, but the time is past for that. And honestly, it was a great lesson for me about drawing when I looked back at it later.

As far as being proud of specific jobs, there are any number I like, but when asked this question, I generally select Manhunter, largely for sentimental reasons. I draw better than that strip now, as it was the first continuity strip I ever did, starting at about six months into my career. But I don’t visually storytell any better now. It’s also true that I’ve never worked with a more simpatico writer than the late Archie Goodwin, who wrote and edited the strip. And I’ve worked with some great writers, so I hope they’ll forgive me for saying that. But Manhunter was also the strip that made me professionally. It won some awards, and before I worked on it I was one more young guy scuffling for work, trying to create a career in comics. After it was over about a year later, I didn’t have to go looking for work again. I had my career.

Johnson: Thanks again so much for your time, Walt. In parting, is there any advice or words of wisdom you could share with the younger generation of creators you’ve inspired over the decades of your career?

Simonson: I taught a comics class for about 11 years over a 20-year period at the School of Visual Arts in NYC. Here’s my class in short. No charge, but don’t tell my former students I’m giving it away for free.

1. Every time you have a question in your work about the comic you’re creating—the writing or the drawing or coloring or lettering or whatever—your direction should always be: Is my answer to this question making my story better? Because that’s what you should be doing in your comics—telling stories to the best of your ability. And whatever your answer, if it isn’t making your story better, you need to rethink it.

2. Use reference. It’ll make your drawing better. There are a million ways to do this, of course. You don’t need to copy or trace a photo, but you need to learn to see the world. What you see, really see, goes through your eyes into your brain, gets scrambled, and comes back out through your hand. So you need to train both your eye and your hand and their interaction with your brain, because that is what makes both training and improvement possible.

3. Comics is hard work. Get used to it.

Write in to the BETA RAY BILL letters page yourself at mheroes@marvel.com and mark it “okay to print." And stay set for BETA RAY BILL #2 on its way next month! Pax et Justitia!

The Daily Bugle

Can’t-miss news and updates from across the Marvel Universe!