'Marvel’s Voices': Christine Dinh on Cindy Moon (Silk) Turning Anger Into Power

“It’s comforting though, I’m never alone, ‘cause [the anger's] always there…always…”

Growing up, I didn’t have many heroes that looked like me; I was impacted like many others by “narrative scarcity,” a tool white supremacy utilized to deprive BIPOCs of stories that could unite us. When groups of people do not see themselves or others don’t see them as part of the story, then it’s hard to see us as people.

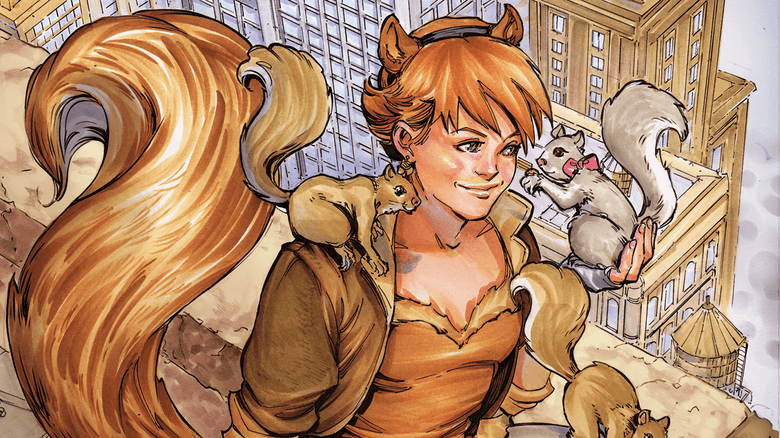

At Marvel, our stories reflect the world outside our windows, including race, gender, and ethnic diversity. We relate to Marvel super heroes because their lives reflect our lives. This includes both the good and the bad. Lately, I’ve been reflecting on Cindy Moon (Silk)‘s origin story and her path to becoming a hero. As a teen, Cindy Moon attended a school field trip with classmate Peter Parker. On that trip, Cindy was bitten by the same radioactive spider that bit Peter, giving her similar powers. Unlike Peter, Cindy and her family, terrified by her newfound powers and to protect her from Morlun and his Inheritors, agreed to have Cindy go underground; literally.

Hidden away for a decade, Cindy was isolated from loved ones and robbed of a “normal” teenage life. This deprivation and isolation initially became a source of frustration and anger for Cindy, something we are all currently familiar with. Cindy, determined and strong, eventually was able to channel this anger into power on her path to becoming a hero and fighting for what was right. Similar to Cindy, I — like so many of us — have spent the last year in my own secluded bunker of sorts due to the ongoing pandemic. This type of isolation is something I would never have imagined my life paralleling in any capacity, but this reality feels like Cindy’s time in that bunker.

Beyond that, this year has given me more and more reasons to be angry at the continuous injustices impacting communities of color. For many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), the concept of racial injustice and racism is something we have dealt with our whole lives. I was nine the first time I heard the phrase “Go back to China” shouted by a neighbor — I was with my mom unloading groceries into our apartment. As a Vietnamese-American born in the United States, I didn’t understand then the vitriol behind those four words, or the very real and sometimes deadly impact that racism and xenophobic rhetoric can have. Now I shun the ingrained desire to deflect and respond with “I’m Vietnamese, not Chinese” — being Asian is not and should never be considered an insult.

Those devasting impacts resulted in a number of incidents of violence against Asian Americans – Asian American women, specifically, in just the last month.

On March 16, 2021, Stop AAPI Hate released a report revealing Asian Americans reported 3,800 hate-related incidents during the pandemic. On the same day, a gunman targeted three Asian American businesses and murdered eight people, including six Asian women in Atlanta. This comes on the heels of other incidents like the deadly attacks on 84-year-old Vicha Ratanapakdee in San Francisco and 75-year-old Pak Ho in Oakland. As a result of this and other incidents, I’m angry. I am angry like Cindy.

It isn’t difficult to trace these actions back to the xenophobic rhetoric amid the Covid-19 pandemic with labels such as “China virus” and “Kung flu” used by the government. This type of rhetoric isn’t new; Asian Americans have had a long history of facing racism and xenophobia in the US, including the fatal beating of Chinese American Vincent Chin in 1982, because two white men “thought” he was Japanese. In addition, the US imposed actions such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Yellow Peril after WWI, and the Japanese internment during WWII.

So, I am angry. Angry that I’ve been isolated from loved ones because of the pandemic unable to comfort them or find comfort in my community, angry that our communities live in fear of being attacked for no reason. And personally, I am angry that my mom, a small business owner who came to this country as a refugee, could easily be a target. I’m angry that the institutions meant to protect us are the same ones harming us – resulting in the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, and countless others. This harm echoes when the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Department said Soon Chung Park, Hyun Jung Grant, Sun Cha Kim, Yong Ae Yue, Delaina Ashley Yaun Gonzalez, Paul Andre Michels, Xiaojie Tan, and Daoyou Feng, lost their lives, not because of racial motivations, but because a man was “lashing out” after a “bad day.” The impact of xenophobia, the continual objectification of Asian women in Western culture, and the erasure of our agency – our “ability” to be angry – can eat away at a person.

Just like the negative impact of the words by the Cherokee County Sheriff, words can have positive power; we can have a positive impact. Today, kids can see themselves through Daisy Johnson, Kamala Khan, Luna Snow, Cindy Moon, and teams like the Agents of Atlas. And, in my role at Marvel, I’m able to elevate the works of our incredible creators such as Alyssa Wong, Maurene Goo, Greg Pak, Preeti Chhibber, Gene Luen Yang, Saladin Ahmed, and so many more.

But there is so much work to be done to stop the harm created by hate and empower our communities to create, and not exist between hushed whispers and private messages.

So we must persevere like Cindy. Cindy with her unique path after being bitten by the same spider as Peter Parker, who hid away for a decade, who left that bunker and channeled her anger, stayed alive, and became strong despite her circumstances. In the same way, I believe our anger and our grief will serve us as well. While our story may be different than Peter’s, our stories matter and we deserve to exist in the same space.

To read more essays from Marvel's Voices on Marvel.com, head over here!

The Daily Bugle

Can’t-miss news and updates from across the Marvel Universe!